Oct 2021 John Tavener

Sept 2021 Vaughan Williams and the Leith Hill Music Festival

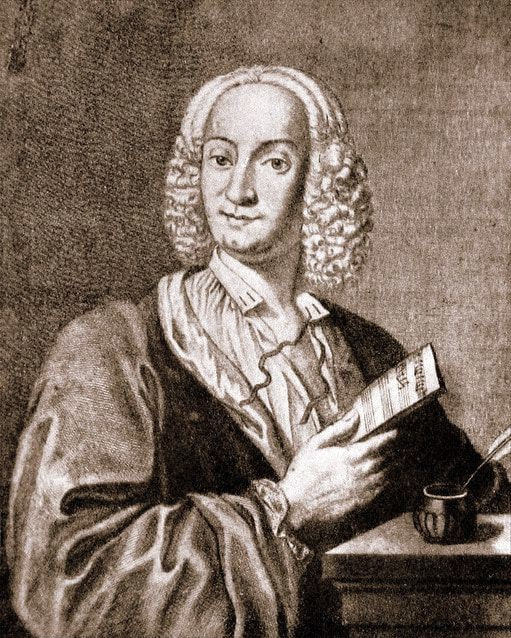

July 2021 Antonio Lucio Vivaldi

June 2021 Musical responses to war - six English composers

May 2021 Ralph Vaughan Williams and Leith Hill Place

April 2021 Film shootings in Surrey and related plays (Part 2)

March 2021 Frank Bridge

Film shootings in Surrey and related plays (Part 1)

Jan 2021 Edric Cundell

Dec 2020 Gerald Finzi

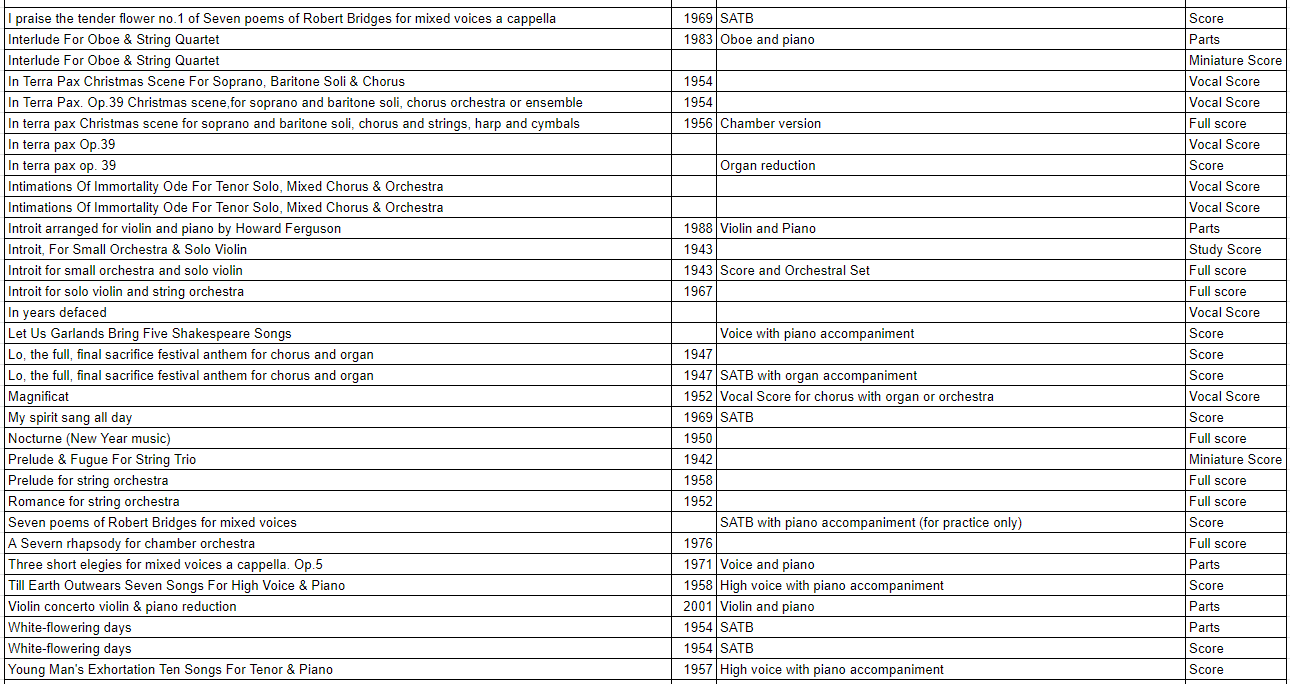

Oct 2020 Rutland Boughton

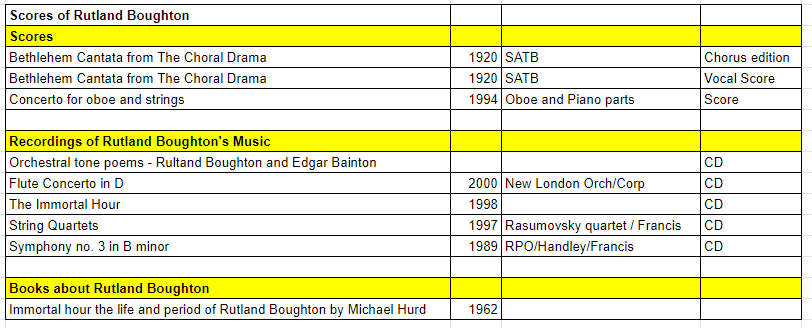

Sep 2020 J. M. Barrie - playwright

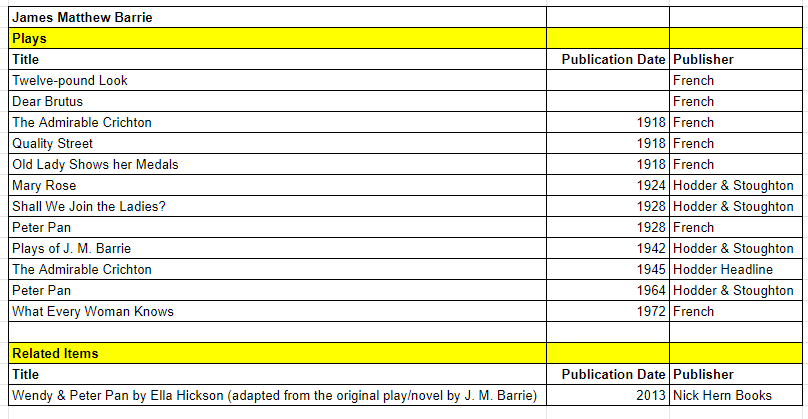

Aug 2020 Samuel Coleridge-Taylor - composer

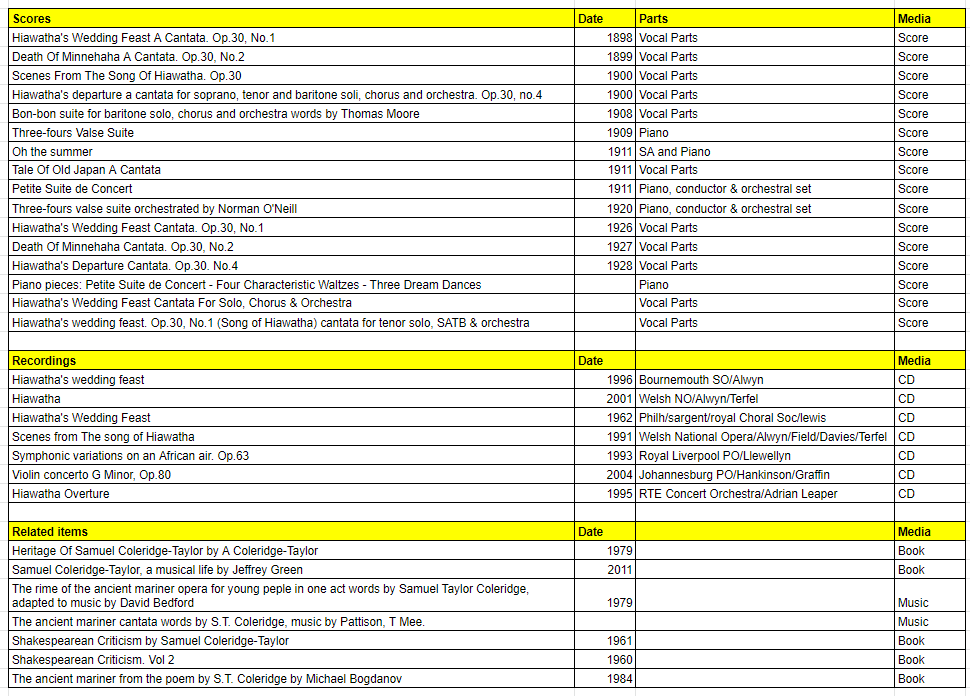

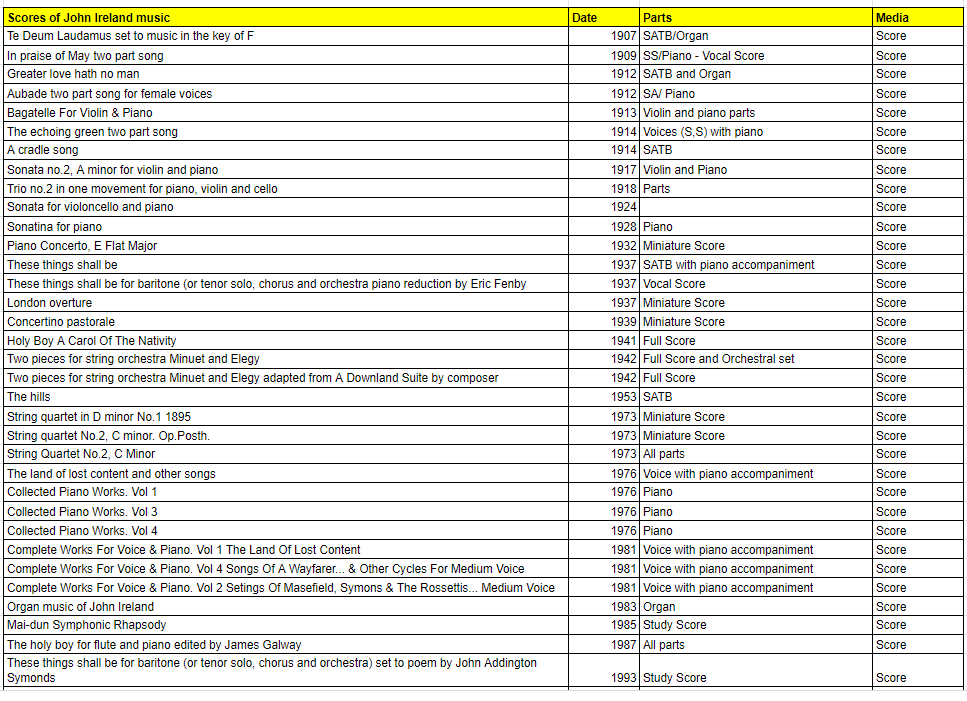

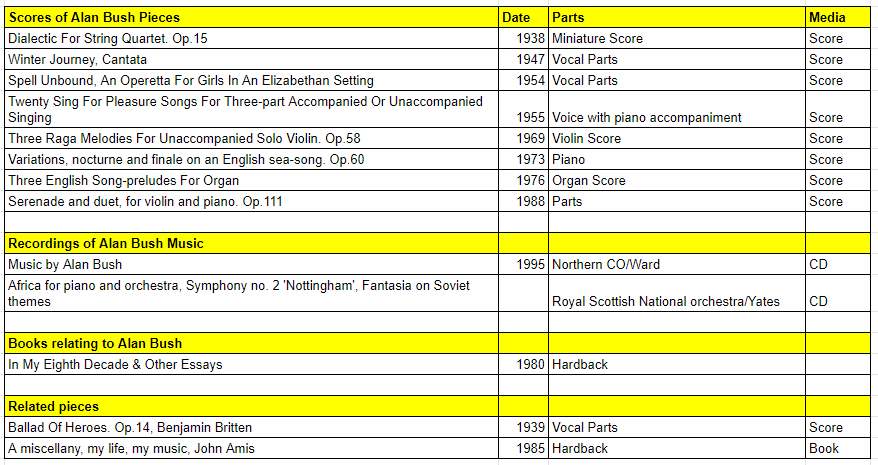

John Ireland - composer

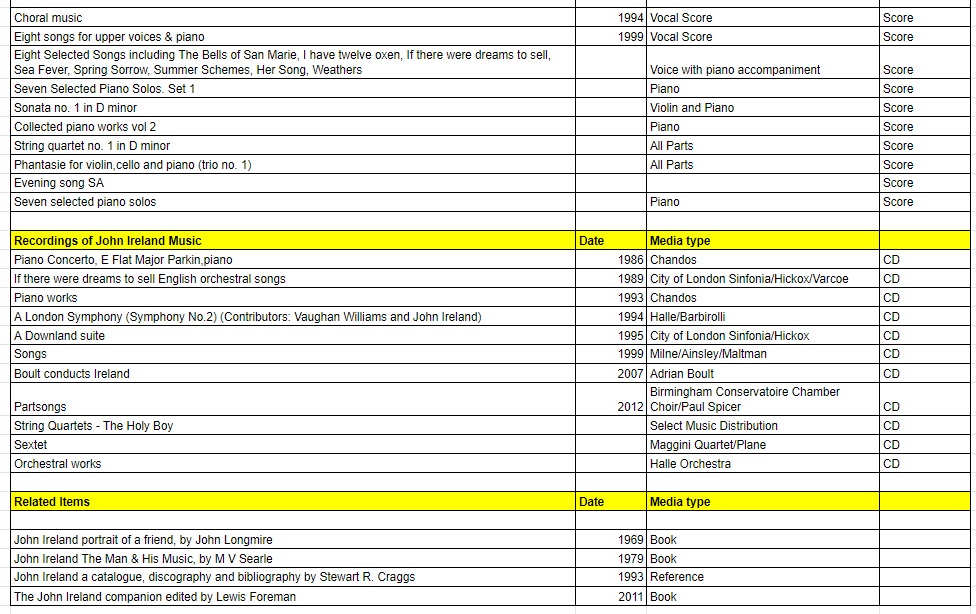

July 2020 John Galsworthy - playwright

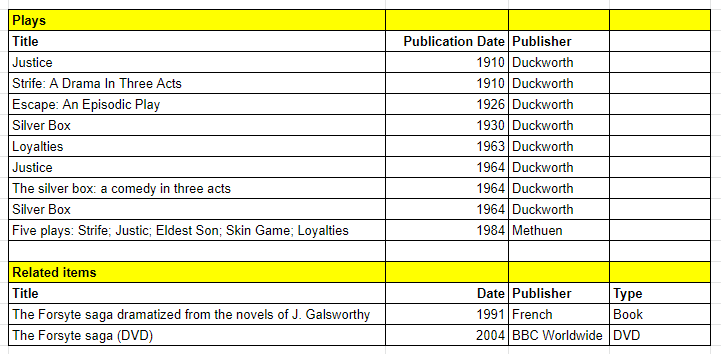

Alan Bush - composer

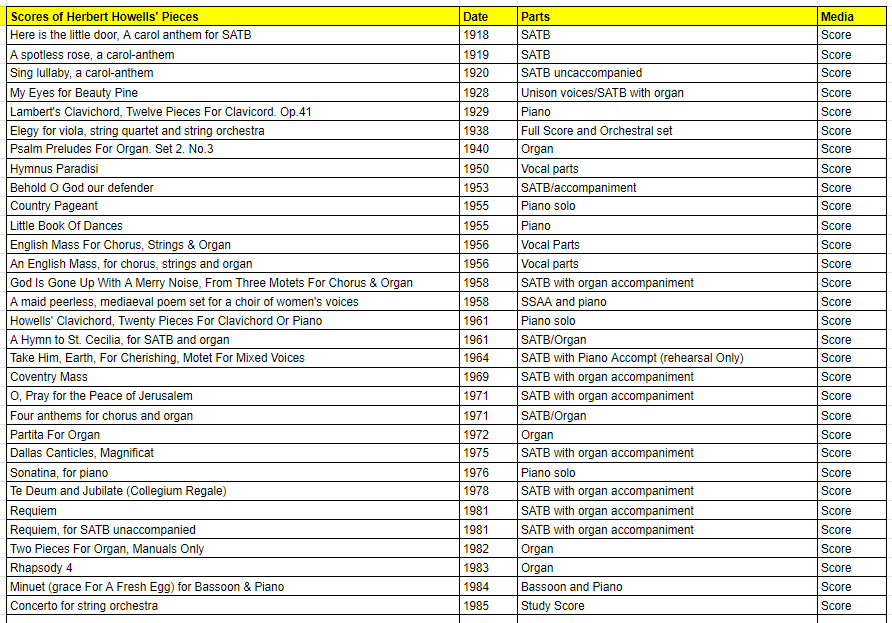

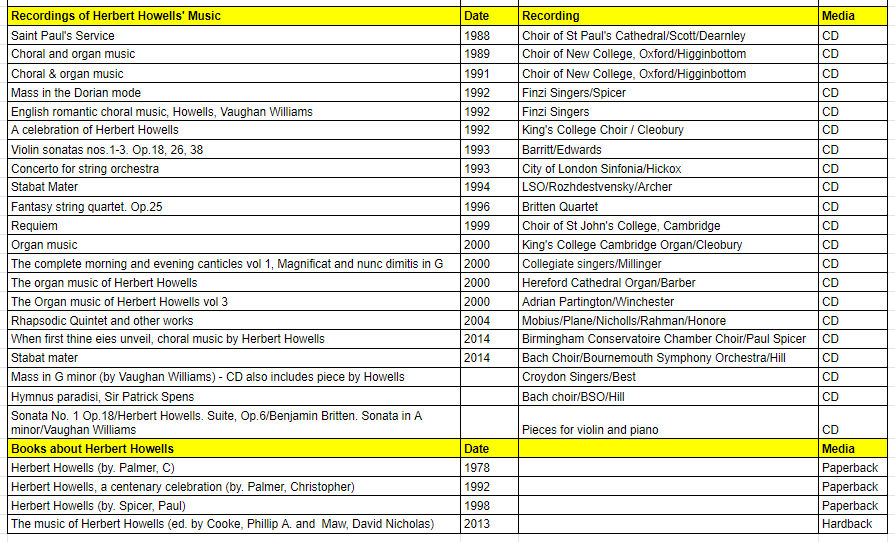

June 2020 Herbert Howells - composer

May 2020 Ethel Smyth - composer

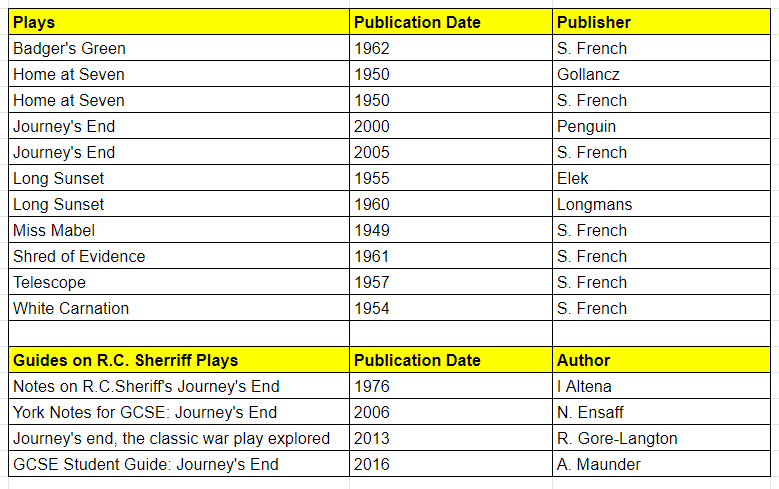

April 2020 RC Sherriff - playwright

Sept 2021 Vaughan Williams and the Leith Hill Music Festival

July 2021 Antonio Lucio Vivaldi

June 2021 Musical responses to war - six English composers

May 2021 Ralph Vaughan Williams and Leith Hill Place

April 2021 Film shootings in Surrey and related plays (Part 2)

March 2021 Frank Bridge

Film shootings in Surrey and related plays (Part 1)

Jan 2021 Edric Cundell

Dec 2020 Gerald Finzi

Oct 2020 Rutland Boughton

Sep 2020 J. M. Barrie - playwright

Aug 2020 Samuel Coleridge-Taylor - composer

John Ireland - composer

July 2020 John Galsworthy - playwright

Alan Bush - composer

June 2020 Herbert Howells - composer

May 2020 Ethel Smyth - composer

April 2020 RC Sherriff - playwright

|

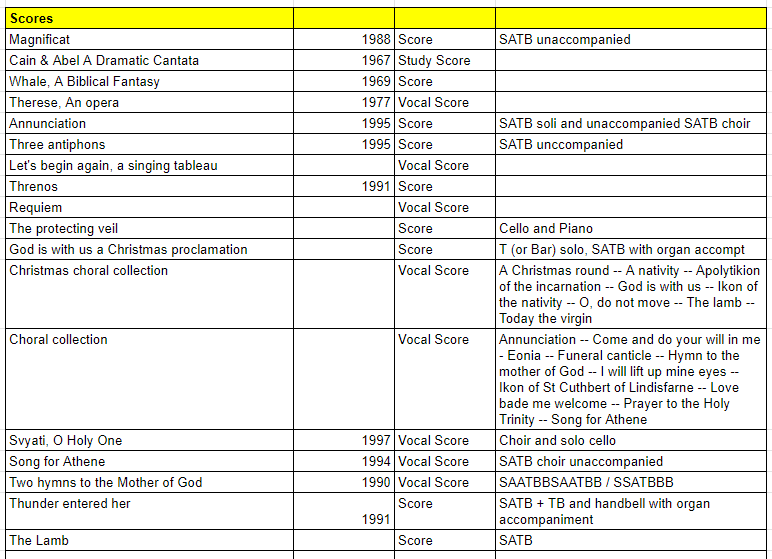

John Tavener (1944-2013)

While at school, John Tavener was introduced to choral singing, became a proficient pianist and also began to compose. In 1962 he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Music, where he eventually gave up the piano to devote himself to composition. He achieved a striking early success with his cantata The Whale. Telling the biblical story of Jonah and the whale, this was a large-scale work, extravagantly scored for choir, soloists and orchestra, plus speakers, loudhailers, pre-recorded tape and amplified metronomes. It was premiered at the inaugural concert of the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, which was also the debut concert of the London Sinfonietta. Among its fans were The Beatles, who arranged for a recording to be issued on their own record label. After leaning initially towards Roman Catholicism, Tavener converted in 1977 to the Greek Orthodox church. His early music had been influenced by Stravinsky and Messiaen (indeed Tavener said it was after a hearing of Stravinsky’s Canticum Sacrum that he determined to become a composer), but after his conversion his music became more sparse, mystical and contemplative. He immersed himself in Greek and Russian culture, and most of his works display a profound religious spirit. Two works in particular achieved a certain popularity. The Protecting Veil, for cello and strings, was performed at the Proms in 1989 to great acclaim. Described by Tavener as ‘a lyrical ikon in sound’, this was a meditative work in which the solo cello represents the Mother of God in a series of musical pictures. A few years later, his elegiac Song for Athene became widely known when it was performed at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997. Regarded now as a major composer, Tavener was knighted in 2000 and he continued to compose music of great originality and imagination. But he had suffered from poor health throughout his life and he died at the age of only 69. He received a large Orthodox funeral in Winchester cathedral. Tavener’s main source of inspiration was his religion. He found a ‘spiritual mother’ in Mother Thekla, an Orthodox nun who co-founded an Orthodox monastery near Whitby in Yorkshire. As well as providing spiritual guidance, she supplied texts for several of his works. In contrast to the more intellectual nature of western religion, Tavener saw the Orthodox faith as something deeper, wilder and untamed. He was more attuned to eastern symbolism and Byzantine culture, and often visited Greece, where he said he felt at home. His style accordingly was contemplative, mystical and transcendental. His music is mainly vocal with small numbers of solo instruments. The vocal lines tend to be repetitive and ritualistic, often influenced by Byzantine chant. He used unconventional instruments such as handbells and gongs. The forms are usually static; there is little or no development of ideas. He often used drones (long-sustained notes or chords) and microtones (intervals smaller than a semitone). In 2003 he wrote The Veil of the Temple, a large-scale work using texts from several religions. Scored for several orchestras, choirs and soloists, it lasts for over seven hours, and Tavener described it as the supreme achievement of his life. Among the performing sets in the library’s collection are Song for Athene, The Lamb, Thunder Entered Her and Svyati. Song for Athene was written in 1993 as a tribute to a family friend, a 26-year-old Greek girl who was killed in a cycling accident. It is a deeply moving elegy for unaccompanied choir. It uses a line from Shakespeare, ‘May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest’, followed by words from the Orthodox burial service. The Lamb is a short piece for unaccompanied choir which was written for the annual Christmas carol service at King’s College, Cambridge in 1982. Setting Blake’s poem ‘The lamb’ from Songs of Innocence, it is a simple homophonic piece, very effective as a Christmas carol. Thunder Entered Her is for choir, handbells and pipe organ, and the text describes the immaculate conception. Svyati has a text in Church Slavonic and it is scored for choir plus a solo cello which represents the Ikon of Christ; the melodic lines recall the chanting of the Orthodox church. Ian Codd Vaughan Williams and the Leith Hill Musical Festival

Ralph Vaughan Williams was conductor of the Leith Hill Musical Festival for almost fifty years. He devoted a great deal of time and energy to the festival, and through his boundless enthusiasm he inspired and encouraged many small choirs and their singers. He also composed several pieces especially for the festival. His legacy remains alive today in the festival itself, still flourishing in Dorking and the surrounding villages, and also in the splendid Dorking Halls which were built to house the festival. Vaughan Williams had a long and close association with the town of Dorking in Surrey. Although he was born in Gloucestershire, his father died when he was only two, and his mother, who was a member of the Wedgwood family, returned to live at the family home of Leith Hill Place, high in the Surrey hills and not far from Dorking. The house was large, with a rather severe and forbidding facade, but it enjoyed a magnificent view over the rolling countryside to the south (it is now owned by the National Trust and is open to the public). Young Ralph showed early musical talent and went on to study at the Royal College of Music in London. In 1885 Mary Wakefield had founded the Westmorland Festival to encourage choral singing in the area and similar festivals were soon springing up all across England. In 1904 Vaughan Williams’ sister Margaret visited the Petersfield Festival with her friend Lady Farrer, and this inspired them to create their own festival. They named it after the highest point in the locality and thus the Leith Hill Musical Festival was born. Its aim was to encourage the many small village choirs in the area by enabling them to sing in competition and then combine to perform a large-scale concert. Vaughan Williams was asked to become the festival conductor and Margaret went on to serve as festival secretary for the next ten years. Vaughan Williams at this point was in his early thirties and not yet well known. In some ways he was a late starter who did not find his true style and musical voice until nearing forty. He was keenly interested in English folk song, of which he collected many examples, and he also had a strong belief in the value of amateur music-making, especially singing. He threw himself into festival work with great energy and enthusiasm, cycling around the village choir rehearsals during the winter months to inspire conductors and singers alike. The first competition and concert took place in 1905 in the Public Hall in Dorking, with seven choirs taking part. During the following years the festival flourished and expanded as more choirs joined in. It was with much sadness that it had to be suspended when war broke out and many men, including Vaughan Williams, were away on active service. After the war the festival resumed. In a rural area where people had only limited opportunities to attend London concerts, and when radio broadcasts were just beginning, Vaughan Williams believed it was important to bring the best of music to as many people as possible. He included a wide range of music in the festival, from Bach to Mussorgsky, and as standards improved he was able to present more ambitious works, including the Verdi Requiem and Elgar’s Gerontius, as well as such classics as Messiah, Elijah and The Creation. Once he had a good orchestra, he was able to conduct symphonies and he did several by Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms, plus some concertos. His convictions were illustrated when there was a debate about extending the festival to include town choirs (some people felt it would alter the nature of the festival) – when asked, Vaughan Williams replied ‘If the towns want to sing, then of course they must!’ The wide experience he gained through working with choirs and attending their rehearsals was also of great benefit to him and his own music: he was able to see at first hand what choirs could and couldn’t do – in short, ‘what worked’. Vaughan Williams was generally reluctant to include his own music in Leith Hill programmes. Not until 1910 was the first VW work included – his short trio Sound sleep for women’s voices. The Sea Symphony was given a memorable performance in 1928 by the Towns division. In 1930, to mark LHMF’s 25th birthday, and the 21st festival, he composed a work especially for each of the divisions – Benedicite for the towns, Three Choral Hymns for div.1, a setting of the Hundredth Psalm for div.2, and Three Songs for Children’s Day. In 1938, with war again threatening, he conducted his cantata Dona Nobis Pacem, a moving prayer for peace and an expression of hope for the future. Vaughan Williams achieved a long-held ambition in 1926 when the Towns division sang parts of Bach’s B minor Mass. He was pleased by the performance and thought that a choir which had reached such a standard deserved a bigger and better hall to sing in. He and the Leith Hill committee began discussing plans to build a new venue with the result that the fine new Dorking Halls, comprising one large hall and two smaller ones, was opened in 1931. The occasion was marked by a special performance of Bach’s St Matthew Passion in an extra festival concert in which singers from all three divisions joined together. Vaughan Williams also gave an illustrated lecture on the music a few weeks beforehand. Eventually there developed a new Leith Hill tradition of performing the St Matthew every year before Easter; Vaughan Williams also conducted it many times with the Bach Choir. When war broke out once more in 1939, the choirs were again depleted in numbers, but Vaughan Williams was determined this time to keep music alive in the area. When smaller choirs were forced to disband, singers joined neighbouring choirs or attended VW’s own weekly rehearsals. When the Dorking Halls were commandeered, concerts were moved instead to St Martin’s church. Many concerts were given there during the war years, often drawing in evacuees from the area. Vaughan Williams, who saw the importance of music as a source of moral support and welcome relief during times of great hardship, displayed his usual energy and enthusiasm. When limitations of space precluded the use of an orchestra, he rescored works for organ and strings. Performances of the St Matthew Passion continued, using an abridged version arranged by Vaughan Williams for strings, organ and piano continuo. For many participants, these annual Passion performances represented more than just a concert; they were a spiritual occasion, almost like a service. (However, Vaughan Williams’ idiosyncratic use of a piano to play the continuo part would certainly not satisfy today’s authentic-performance standards!) In 1949 a special concert took place at the Dorking Halls, given by friends of the LHMF to Vaughan Williams. VW conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in his Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus plus his London Symphony and William Cole, who had been appointed assistant festival conductor the previous year, conducted the sixth symphony. Another special concert was given in 1951, jointly with the Surrey Philharmonic Orchestra, as part of the Festival of Britain. Vaughan Williams resigned as festival conductor in 1953 - he was, after all, now eighty years old! - and was succeeded by William Cole. In 48 years and despite his very busy professional life, he had rarely missed a rehearsal and never missed a festival concert. By now a national figure – indeed his country’s leading composer - he became president of the festival and was invited back as guest conductor. In 1954 each of the festival concerts included one of his choral works, conducted by the composer, and his music has featured prominently in the festival ever since. For many years, the competitions began with a sight-singing test (often dreaded by the singers!) and choirs had suggested having a short piece to ‘sing themselves in’ beforehand. So Vaughan Williams wrote his Song for a Spring Festival, for the sole exclusive use of Leith Hill. Although the sight-singing class has long disappeared (to the great relief of many singers!), the Spring Song is still sung by the combined choirs at the beginning of each festival day, serving as a small but enduring reminder of the generous man and great composer who gave so much to the Leith Hill Musical Festival. Ian Codd

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi

Surrey Performing Arts Library holds 385 copies of Vivaldi’s Gloria in the Ricordi edition edited by Alfredo Casella, 99 in the edition by Walton Music, 74 in the Oxford University Press edition and 29 in an edition by Lawson-Gould. There are also 40 copies of an arrangement for women’s voices published by Novello. That’s 627 in total. How did this setting of the Gloria text from the Latin Mass composed for an orphanage for young girls in Venice in around 1715 come to be so popular? Well, the answer is, to a large degree, by chance. Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in Venice in 1678, the second child and first son of Camilla Calicchio and Giovanni Battista Vivaldi, a barber of humble origins turned successful violinist. At the age of fifteen it was decided that Antonio should study for the priesthood probably not from any strong vocation but chosen as a route whereby his own status and that of the whole family could be raised. He had suffered from birth from a condition that affected his everyday mobility – thought to be bronchial asthma – and it was probably always envisaged that he would become a secular priest or abate not attached to any particular church or order. In the event, he was relieved of the obligation to say Mass soon after his ordination. However, his ability to play the violin does not appear to have been affected. It is assumed that Antonio received most of his musical training from his father with whom he is known to have played as a supernumerary violinist at St Mark’s. It was in about 1703 when he was first employed as a violin teacher at the Ospedale della Pietà, one of four large orphanages in Venice. The Pietà catered for foundling girls and with a resident population of around 1,000 maintained a substantial musical establishment or coro, larger than any of the other ospedali. The ospedali had an interest in maintaining the standard of their cori for reasons of prestige and to attract legacies and donors, and the figlie de coro included very accomplished musicians who had chosen to stay on after reaching adulthood. Vivaldi was to be associated with the Pietà for much of his life. During the 1710s his role with the Pietà began to change from that of an instrumental teacher to that of a composer providing, initially, sacred vocal music such as the Gloria. Teaching posts at the ospedale were on the basis of annually renewable contracts and there were periods when he wasn’t re-appointed so Vivaldi necessarily had other sources of income. His music – violin sonatas and trio sonatas - began to appear in print, first locally in Venice and then later published by Estienne Roger in Amsterdam. He also developed a business selling his compositions in manuscript both locally and further afield and giving lessons to visiting noblemen and their entourages. His other main interest was the composition and production of operas, in which he was joined as an impresario by his father. By the 1730s Vivaldi’s career in Venice had begun to decline and in the Summer of 1740 he left for Vienna, possibly hoping to gain employment with the Hapsburg Emperor Charles VI whom he had met in Trieste in 1728. If that was the plan it came to nothing; Charles died unexpectedly after eating poisonous mushrooms in September 1740 and the ensuing year-long period of mourning left Vivaldi stranded in Vienna without the resources to return to Venice. He was to die there himself in July 1741. After his death Vivaldi’s reputation as a composer quickly receded and during the 19th century if his name was mentioned at all it was usually only in connection with keyboard transcriptions by J S Bach of some of his violin concertos. It seems that Vivaldi’s personal collection of manuscripts was sold from his estate to a Venetian collector, Jacopo Soranzo. After Soranzo’s death in 1761 the collection was dispersed and then brought together again by the Jesuit and collector Abbot Matteo Luigi Canonici and sold to a Count Giacomo Durazzo in the late 1700s. On Durazzo’s death in 1794 the manuscripts were moved from Venice to the family’s villa in Genoa. The Durazzo collection was eventually divided between two brothers and in 1922 Marcello Durazzo died and left his part of the collection to the Salesian monks of Collegio San Carlo in San Martino near Turin. The monks, wishing to sell the manuscripts, were referred for advice to Alberto Gentili, professor of music history at University of Turin. Realising the significance of the collection of hundreds of unknown compositions by Vivaldi and other composers, Gentili arranged for it to be purchased in 1927 for the National University Library in Turin by Roberto Foà, a banker, as a memorial to his deceased infant son. On examining the manuscripts, Gentili could now see that they were only part of an original collection. A search was made and the missing manuscripts were found to be with Marcello’s nephew Giuseppe Maria. After prolonged negotiations Gentili arranged their purchase in 1930 for the National University Library by Filippo Giordano, a textile manufacturer, in memory, as with Foà, of his deceased son. However, this was subject to a stipulation from Giuseppe Maria that no publication or performance of the music would be allowed. After much legal manoeuvring the stipulations were laid aside in 1938. It was the Giordano collection that contained the single surviving score of the Gloria. At this point, because of the rise of the Fascist Party in Italy and its anti-Jewish laws, Gentili, who was Jewish, disappeared from the picture. He was forced from public life and dismissed from his post at the university. Now interest in the Vivaldi manuscripts centred on the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena led by the composer, conductor and pianist Alfredo Casella, who was in favour with the Fascists. Two other key figures in Vivaldi’s rediscovery were the controversial American poet and critic Ezra Pound and Pound’s mistress Olga Rudge, an American born violinist who worked as an administrator at the Accademia. Rudge catalogued the Turin manuscripts and Pound visited Dresden to research a cache of manuscripts of instrumental music found in 1860 in a cabinet behind the organ in Dresden’s Hofkirche, where they had lain overlooked for a century. In September 1939 a Vivaldi Festival Week was organised by the Accademia in Siena which included the first modern performances of the Credo RV 591 for choir and orchestra, the Stabat Mater RV 621 for alto solo and strings, and the Gloria RV 589[i]. However, reaction to the festival was overshadowed by the outbreak of World War II. After the war in 1947 the Istituto Italiana Antonio Vivaldi was founded by Antonio Fanna to promote Vivaldi’s music and, with Ricordi Publishing, began the publication of a complete edition of the composer’s music. Casella’s edition of the Gloria as used in 1939 had been published in 1941. A more accurate edition by Gian Francesco Malpiero was published in 1957 and the work made its US premiere at Brooklyn College’s first Festival of Baroque Music in the same year. A key moment in the growing popularity of the Gloria in the UK was the release in 1967 of a recording, still available, by the choir of King’s College, Cambridge and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields under David Willcocks with Elizabeth Vaughan and Janet Baker as the soloists. Since then, the Gloria, having disappeared completely together with most of Vivaldi’s other music for nearly two hundred years and only rediscovered through a series of fortuitous events, has become a staple of concert programmes. The varied sequence of a dozen choruses and solos designed by Vivaldi to attract influential visitors to the Pietà continues to delight both singers and audiences. [i] There are two surviving settings of the Gloria by Vivaldi. The by far better known is RV589. The other, which is on a larger scale and is prefaced with an introductory motet for solo soprano which interleaves with the opening bars of the first movement, is RV 588. RV stands for ‘Répertoire Vivaldien’, the comprehensive catalogue of Vivaldi’s work created by the Danish scholar Peter Ryom. As there are so many Vivaldi items in the catalogue we have condensed them into a spreadsheet.

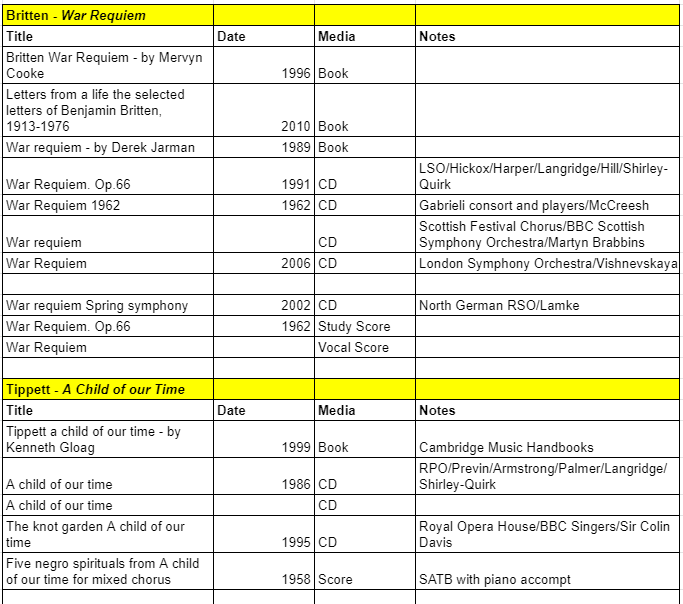

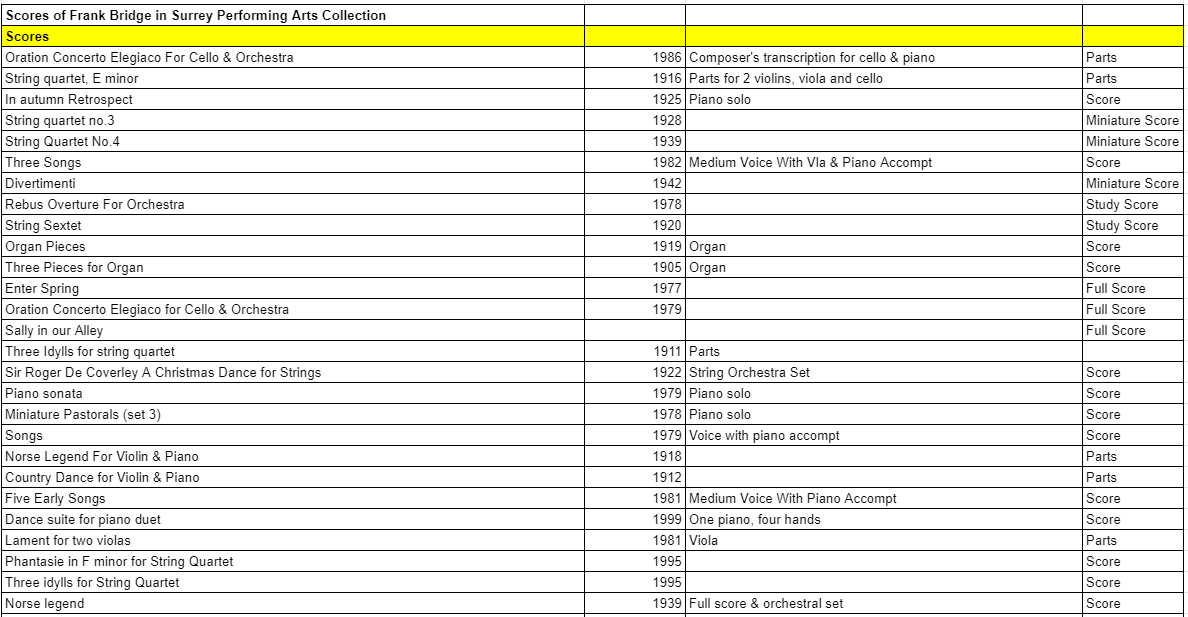

Musical responses to war – six English composers

This article explores responses to the two world wars in choral works by six English composers: Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, Edward Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss and Gustav Holst. Sets of vocal scores of all the works discussed (except for Bliss) are held in the library. History has of course seen numerous wars, many of them horrific and brutal, but the twentieth century saw the invention of mechanised warfare with mass slaughter on an industrial scale. The dead of the two world wars were numbered in millions, indeed tens of millions worldwide, and countless more were maimed and injured or mentally scarred. Many of the dead were little more than boys, who had gone off cheerfully and innocently to fight for their country, little dreaming they would never see their homes again. It is hardly surprising that composers responded to these events with some deeply moving music. Perhaps the greatest of these works is Britten’s War Requiem, written for the consecration of the new Coventry cathedral and performed there in 1962. In a gesture of reconciliation, Britten wrote the three solo parts for leading singers from three of the warring nations and former enemies: the English tenor Peter Pears, the German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya. However, the Soviet authorities, to their enduring shame, refused to allow Vishnevskaya to travel abroad and her part was taken at the first performance by Heather Harper. Britten had the inspired idea of interspersing the sections of the Requiem Mass with poems by Wilfred Owen. Owen was one of the greatest poets of the first world war; he was killed in action in 1918, just a week before the Armistice. His poems are sung by the two male soloists with a small chamber orchestra, while the music of the Requiem is performed by the choir, boys’ chorus, soprano and very large orchestra. Britten held strong pacifist views and was a conscientious objector during the second world war, and the War Requiem is a very personal expression of his beliefs. Much of the music is of searing intensity and hearing the entire work is a deeply emotional experience. Its final section, the Libera Me, includes a setting of Owen’s poem ‘Strange meeting’, with its haunting line ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend’, followed by the beautiful and consoling In Paradisum. Another composer who was a conscientious objector, and who spent time in prison for his beliefs, was Tippett. The story of his oratorio A child of our time is based on historical events. In Paris in 1938, a young boy, a Polish Jew, fleeing the Nazi terror, shot and killed a German official; in retaliation the Nazis launched a vicious pogrom against the Jews, the infamous Kristallnacht. Tippett, writing his own libretto, universalized these events to depict the persecution of the outcast. He modelled the structure of his oratorio on the tri-partite design of Handel’s Messiah, and from the Lutheran passions he took the elements of recitative, aria and chorus. But he struggled to find an adequate equivalent to the Lutheran chorale, something that would resonate with a modern audience. One day, listening to the radio, he heard the spiritual Steal away and knew that he had found his answer; the five spirituals from A child of our time are now often performed independently. The other theme of the oratorio is the need to reconcile opposites, which Tippett took from the psychology of Jung. Each individual must come to terms with the light and dark sides of his own personality in order to become whole. The oratorio itself progresses from winter to spring, from darkness to light, and it ends with the words of the spiritual Deep river: ‘Lord, I want to cross over into camp ground’. Elgar produced an early musical response to the first world war in his choral work The spirit of England, setting poems by Laurence Binyon. During the first months of war in 1914, Binyon produced a dozen poems, from which Elgar selected three, setting them for soprano or tenor solo, choir and orchestra. Binyon’s words were written before the full horror of war became apparent and Elgar’s music expresses the national mood of the time. The first movement (The fourth of August) expresses something of the optimism with which the first troops set off to fight for freedom, sustained by ‘the spirit of England, ardent-eyed’. By contrast, the third movement (For the fallen), with its steady funereal tread, is a requiem for the fallen. Setting Binyon’s now-famous lines, it mourns the dead and declares ‘we shall remember them’. The music is stately and solemn, sorrowful yet noble, with broad choral writing, march rhythms, and soaring melodic lines. Impressive though the piece is, it is more of a public than a private statement, and perhaps Elgar’s most personal and poignant war music was in his cello concerto, a deeply elegiac work written immediately after the war. Vaughan Williams served in the first world war as a medical orderly, witnessing some of the horrors at first hand. He wrote his choral work Dona nobis pacem in 1936 when there were growing fears of another approaching war. It combines the poetry of Walt Whitman with words from the Bible in a manner that foreshadows Britten’s War Requiem some 25 years later. Whitman’s words were inspired by the American civil war, while Vaughan Williams was obviously recalling his own experiences. Dona nobis pacem is both a prayer for peace and a depiction of the horror and the sorrow of war. Among its six sections, the second, with its noisy drums and bugles, is a kind of Dies Irae, depicting the cruelties of war. Then comes ‘Reconciliation’, a moving piece for baritone and choir which foreshadows the ‘Strange meeting’ near the end of Britten’s War Requiem. The ‘Dirge for two veterans’ is a mournful reflection on death and needless sacrifice. The finale begins quietly with hopes for the future; as bells and percussion join in, it celebrates the glory of God’s kingdom and then concludes with a final quiet prayer for peace. Another composer who served in the first war was Arthur Bliss. His younger brother Kennard was killed on the Somme in 1916, and Morning Heroes was written in 1930 as a tribute to him. It also helped Bliss to exorcise his own nightmare memories of wartime experiences. Written for chorus and orchestra, plus a narrator, it draws its texts from Homer, Whitman, Li-Tai-Po, Wilfred Owen and Robert Nichols. These are used to explore various aspects of war, especially heroism. In the first section, the narrator reads the moving farewell between Hector and his wife Andromache, from the Iliad. Hector is going to battle, where he will be slain by Achilles. Subsequent movements describe the spirit of self-sacrifice of the thousands who volunteered to fight in 1914; the sad thoughts of a young wife, left alone at home and concerned for her husband; and a soldier on watch, thinking longingly of home. The final section concerns the battle of the Somme, in which Kennard Bliss died. The narrator reads Owen’s ‘Spring offensive’, which describes a young soldier waiting to advance into no-man’s-land, and finally the chorus sings of sunrise over the scarred battlefield, with its ‘companies of morning heroes’. Holst was deeply affected by the first world war, although he was declared unfit for military service and therefore spared first-hand experience of the battlefield himself. He produced a small masterpiece in A dirge for two veterans, for male voices and piano (or brass and percussion). Written in 1914, it reflects the carnage at the beginning of the war. Holst evokes a cold moonlit scene where a father and son, two veterans fallen together, are being taken for burial in the double grave that awaits them. Alongside the slow sad tread of the vocal lines, drum taps and bugle calls are heard in the piano part. Holst also depicted the horror of modern warfare in ‘Mars, the bringer of war’, the first movement of his suite The planets. Here is presented the brutality of mechanised war, in relentless pounding rhythms in 5/4 time. Written by Ian Codd | |||||||

Ralph Vaughan Williams and Leith Hill Place

After the early death of her husband, Arthur Vaughan Williams, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ mother Margaret brought her young family back to live with her parents Josiah Wedgwood III and Caroline (nee Darwin) at Leith Hill Place. Ralph was two and a half years old.

Ralph was brought up surrounded by the beauty and tranquillity of the Surrey Hills and his appreciation of this was a recurring theme in his music throughout his life. His aunt Sophy taught him to play the piano and he also learnt the violin, viola and organ. In 1880, when he was just eight, he took a correspondence course in music from Edinburgh University and passed the associated examinations. He went to school at nearby Charterhouse in Godalming before attending the Royal College of Music and then on to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied music and history.

He returned to the Royal College of Music to study with Sir Hubert Parry (composer of 'Jerusalem') and to specialise in composition. He also studied for short periods with Bruch in Berlin and Ravel in Paris before developing his unique English style. Ralph Vaughan Williams became one of the most prolific English composers of the 20th-century. He composed nine symphonies and numerous choral and chamber works, as well as film scores, operas, music for ballet and theatre, solo songs, song cycles and instrumental pieces.

He collected English folk songs and this strongly influenced his style. His romance for violin, The Lark Ascending, has regularly been voted the nation's favourite classical piece by Classic FM. Just as importantly, he was a teacher, lecturer, conductor, writer and friend to other composers and musicians, most notably his great friend was Gustav Holst.

He composed The Lark Ascending just before the First World War, but its first performance was not until after the war. At the start of the war, he volunteered as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps. After a time as a stretcher bearer in France and Salonika, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery and found himself in charge of both guns and horses. Following the war, he wasn’t demobbed until 1919.

He had a life-long passion for Shakespeare and the music of J S Bach. He was a strong believer that everyone should have music in their lives. He edited the English Hymnal and supported his sister, Margaret, in the formation of the Leith Hill Musical Festival. He often took part as a composer and conductor. He urged people to make their own music, however simple. Vaughan Williams was a modest man who wanted his legacy to be the music he left behind.

Leith Hill Place, like so many National Trust places, has been closed throughout the pandemic. However, it will reopen on a limited basis from Friday, 21 May by prebooked ticket.

To find out further details and the most up to date information, including how to book, please see the website: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/leith-hill-place

After the early death of her husband, Arthur Vaughan Williams, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ mother Margaret brought her young family back to live with her parents Josiah Wedgwood III and Caroline (nee Darwin) at Leith Hill Place. Ralph was two and a half years old.

Ralph was brought up surrounded by the beauty and tranquillity of the Surrey Hills and his appreciation of this was a recurring theme in his music throughout his life. His aunt Sophy taught him to play the piano and he also learnt the violin, viola and organ. In 1880, when he was just eight, he took a correspondence course in music from Edinburgh University and passed the associated examinations. He went to school at nearby Charterhouse in Godalming before attending the Royal College of Music and then on to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied music and history.

He returned to the Royal College of Music to study with Sir Hubert Parry (composer of 'Jerusalem') and to specialise in composition. He also studied for short periods with Bruch in Berlin and Ravel in Paris before developing his unique English style. Ralph Vaughan Williams became one of the most prolific English composers of the 20th-century. He composed nine symphonies and numerous choral and chamber works, as well as film scores, operas, music for ballet and theatre, solo songs, song cycles and instrumental pieces.

He collected English folk songs and this strongly influenced his style. His romance for violin, The Lark Ascending, has regularly been voted the nation's favourite classical piece by Classic FM. Just as importantly, he was a teacher, lecturer, conductor, writer and friend to other composers and musicians, most notably his great friend was Gustav Holst.

He composed The Lark Ascending just before the First World War, but its first performance was not until after the war. At the start of the war, he volunteered as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps. After a time as a stretcher bearer in France and Salonika, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery and found himself in charge of both guns and horses. Following the war, he wasn’t demobbed until 1919.

He had a life-long passion for Shakespeare and the music of J S Bach. He was a strong believer that everyone should have music in their lives. He edited the English Hymnal and supported his sister, Margaret, in the formation of the Leith Hill Musical Festival. He often took part as a composer and conductor. He urged people to make their own music, however simple. Vaughan Williams was a modest man who wanted his legacy to be the music he left behind.

Leith Hill Place, like so many National Trust places, has been closed throughout the pandemic. However, it will reopen on a limited basis from Friday, 21 May by prebooked ticket.

To find out further details and the most up to date information, including how to book, please see the website: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/leith-hill-place

Action, Camera, Roll - Shooting in Surrey! (Part 2)

Continuing a look at films that have used beautiful Surrey location.

Film Title: The Invisible Woman (2013)

Location: Devil’s Punch Bowl, Hindhead, Southside House in Wimbledon

This film, directed by Ralph Fiennes is all about Charles Dickens. The Hindhead location is used to represent Hampstead Heath, just why is something of a mystery!

There are quite a lot of sets containing adaptations from Dickens in the library. All are “full plays” – i.e. with more than one act, unless specifically noted.

Adaptations for children:

Coles, Hylton, Three plays from Dickens Blackie & Son, 12 copies

Hardwick, Michael, Plays from Dickens, Murray 24 copies

Williams, Guy, Pip & The Convict, Macmillan, One Act Play, 12 copies

Adaptations of A Christmas Carol

Bedloe, Christopher, A Christmas carol, Samuel French, 7 copies

Brittney, Lynn, A Christmas Carol, Playstage,11 copies

Cox, Constance, A Christmas Carol, Warner-Chappell, One Act Play, 7 copies

Foss, Kenelm, A Christmas Carol, Samuel French, 18 copies

Hardwick, Michael, A Christmas Carol, Davis-Poynter, 8 copies

Mortimer, John, Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, Samuel French, 9 copies

Adaptations of A Tale of Two Cities

Burton, Brian A tale of two cities, Hanbury Plays, 14 copies

Fitzgibbons, Mark, Charles Dickens' A tale of two cities, Baker's Plays, 18 copies

Francis, Matthew A tale of two cities, Samuel French 13 copies

Adaptations of other novels

Jeffreys, Stephen, Hard Times, Samuel French, 8 copies

Williams, Guy, Oliver Twist, Macmillan, 15 copies

Williams, Guy, David Copperfield, Macmillan, 10 copies

Williams, Guy, Nicholas Nickleby, Macmillan, 15 copies

Film Title: Macbeth (2015)

Location: Hankley Common, Elstead

Filmed in 2014 to celebrate Shakespeare’s 450th birthday by Justin Kutzel, the film stars French Oscar-winner Marion Cotillard and Michael Fassbender.

In the library we have the following. All are different:

Macbeth (Players' Shakespeare), Heinemann, 12 copies

Macbeth (New Penguin Shakespeare), 15 copies

Macbeth, Dramascript Classics, 23 copies

Film Title: Pride and Prejudice and Zombies - yes, you did read that right!

Location: Frensham Ponds, near Farnham

Jane Austen's classic tale of the tangled relationships between lovers from different social classes in 19th century England is faced with a new challenge - an army of undead zombies. Dog walkers at Frensham Little Pond were treated to full blood and gore covered costume action for this American horror movie. It’s a parody of Jane Austen’s 1813 novel. You may well be pleased to know that we do not have the filmscript in the library. However, we do have adaptations of the original!

Cox, Constance, Pride and Prejudice, Garnet Miller 13 copies

Jerome, Helen, Pride and Prejudice, Samuel French, 48 copies

Kennett, John, Pride and Prejudice, Blackie, 19 copies.

Continuing a look at films that have used beautiful Surrey location.

Film Title: The Invisible Woman (2013)

Location: Devil’s Punch Bowl, Hindhead, Southside House in Wimbledon

This film, directed by Ralph Fiennes is all about Charles Dickens. The Hindhead location is used to represent Hampstead Heath, just why is something of a mystery!

There are quite a lot of sets containing adaptations from Dickens in the library. All are “full plays” – i.e. with more than one act, unless specifically noted.

Adaptations for children:

Coles, Hylton, Three plays from Dickens Blackie & Son, 12 copies

Hardwick, Michael, Plays from Dickens, Murray 24 copies

Williams, Guy, Pip & The Convict, Macmillan, One Act Play, 12 copies

Adaptations of A Christmas Carol

Bedloe, Christopher, A Christmas carol, Samuel French, 7 copies

Brittney, Lynn, A Christmas Carol, Playstage,11 copies

Cox, Constance, A Christmas Carol, Warner-Chappell, One Act Play, 7 copies

Foss, Kenelm, A Christmas Carol, Samuel French, 18 copies

Hardwick, Michael, A Christmas Carol, Davis-Poynter, 8 copies

Mortimer, John, Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, Samuel French, 9 copies

Adaptations of A Tale of Two Cities

Burton, Brian A tale of two cities, Hanbury Plays, 14 copies

Fitzgibbons, Mark, Charles Dickens' A tale of two cities, Baker's Plays, 18 copies

Francis, Matthew A tale of two cities, Samuel French 13 copies

Adaptations of other novels

Jeffreys, Stephen, Hard Times, Samuel French, 8 copies

Williams, Guy, Oliver Twist, Macmillan, 15 copies

Williams, Guy, David Copperfield, Macmillan, 10 copies

Williams, Guy, Nicholas Nickleby, Macmillan, 15 copies

Film Title: Macbeth (2015)

Location: Hankley Common, Elstead

Filmed in 2014 to celebrate Shakespeare’s 450th birthday by Justin Kutzel, the film stars French Oscar-winner Marion Cotillard and Michael Fassbender.

In the library we have the following. All are different:

Macbeth (Players' Shakespeare), Heinemann, 12 copies

Macbeth (New Penguin Shakespeare), 15 copies

Macbeth, Dramascript Classics, 23 copies

Film Title: Pride and Prejudice and Zombies - yes, you did read that right!

Location: Frensham Ponds, near Farnham

Jane Austen's classic tale of the tangled relationships between lovers from different social classes in 19th century England is faced with a new challenge - an army of undead zombies. Dog walkers at Frensham Little Pond were treated to full blood and gore covered costume action for this American horror movie. It’s a parody of Jane Austen’s 1813 novel. You may well be pleased to know that we do not have the filmscript in the library. However, we do have adaptations of the original!

Cox, Constance, Pride and Prejudice, Garnet Miller 13 copies

Jerome, Helen, Pride and Prejudice, Samuel French, 48 copies

Kennett, John, Pride and Prejudice, Blackie, 19 copies.

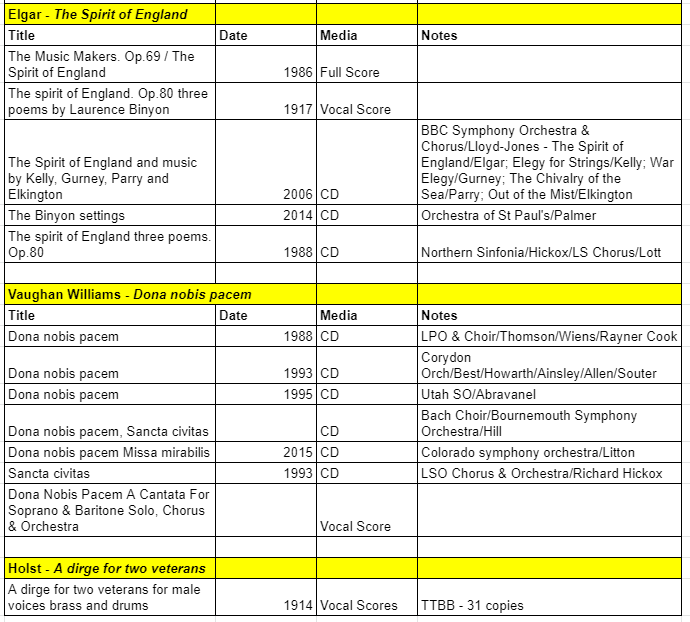

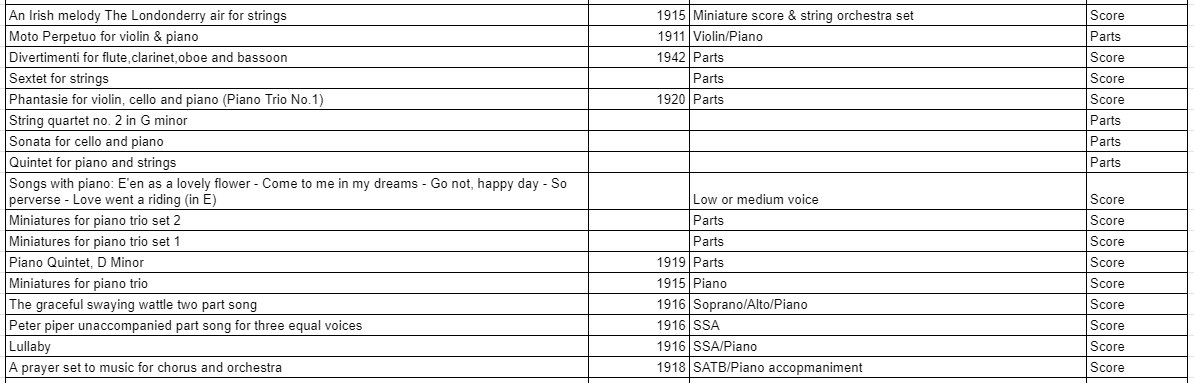

Frank Bridge (1879-1941)

Frank Bridge was a fine all-round musician. He was an excellent viola player and member of a string quartet, a capable conductor and a talented composer. Unjustly neglected after his death, he has become better known in recent years, though still only for a handful of works. He was an important British composer of the twentieth century and his music deserves greater appreciation and recognition.

He was born in Brighton, being the ninth child of a modest family. His father, a keen musician, gave up his job as a printer to become a violin teacher and conductor of a theatre orchestra. Young Frank was made to learn the violin and subjected to long hours of practice. He entered the Royal College of Music and though his first few years were undistinguished, he won a scholarship to study composition with Stanford. He then developed rapidly as a composer and also took up the viola, soon becoming a fine player. On leaving the college, he earned his living as a teacher and performer. He played in three string quartets, most notably the English String Quartet which became one of the country’s finest chamber groups. At this time he composed a good deal of chamber music, along with songs, other vocal works and piano pieces. His style was easy-going, with a ready appeal to the public, and he began to make his reputation. Especially popular was his four-movement orchestral suite The Sea. He also became known as a reliable conductor, often called on to deputise at the last minute when someone was indisposed.

Then came the first world war. Bridge was a pacifist by inclination and he was horrified by the violence of the war and the slaughter in the trenches. He seems to have passed through a personal crisis and his musical style changed significantly. After the war, his music became deeper and more personal in tone. Influenced perhaps by the more modern music emerging in continental Europe, it also became more advanced and dissonant, more radical in style. At the same time, owing to the aftermath of war, Bridge found his income reduced and was forced to undertake more teaching, leaving him less time and energy for composition.

His fortunes changed with the appearance of an American patroness. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge was a wealthy heiress who spent vast sums on music, organising concerts and festivals of chamber music and commissioning new works. She met Bridge in England in 1922, they became friends, and soon Bridge and his wife joined Mrs Coolidge for a tour of France, all at her expense. The following year they sailed for New York to take part in her festival, after which Bridge enjoyed a month’s tour of America, conducting various orchestras. Though Bridge was grateful for Mrs Coolidge’s support, he did not want to become permanently indebted to her and he initially turned down her offer of an annual payment; later however, he accepted it with gratitude. Now that he had been given the gift of financial security, he could return home to England and compose as he wished.

Though his home had been for some time in London, Bridge was fond of Sussex and he enjoyed walking on the south downs. His creativity was nourished by the landscape and by its proximity to the sea, and so he and his wife had a house built near Friston with a view of the downs. Here Bridge devoted himself to composition, producing many outstanding works, such as his third and fourth string quartets, his second piano trio and violin sonata, the orchestral Enter spring and There is a willow grows aslant a brook, Phantasm for piano and orchestra, and his one-movement cello concerto Oration. These works had less appeal for the public and Bridge died in relative obscurity, aged only 62, after suffering poor health.

Alongside his achievements as a composer, now happily receiving greater recognition, Frank Bridge is also remembered as the teacher of Benjamin Britten. Britten first heard Bridge’s music as a young boy when he attended a Norwich Festival concert and heard Bridge conduct The Sea. As Britten said, he was ‘knocked sideways’ by it. A few years later he began taking composition lessons with Bridge and a close friendship developed between the two. Britten remembered his teacher as strict and demanding, one who imposed high standards, but he also enjoyed his wide-ranging conversations, embracing music, art and literature. While Britten was at the Royal College he visited the Bridges at home in London, and later Frank would drive him around Sussex, introducing him to the beauty of the countryside. Britten left a permanent musical tribute to his teacher in his orchestral Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge.

Written by Ian Codd

Frank Bridge was a fine all-round musician. He was an excellent viola player and member of a string quartet, a capable conductor and a talented composer. Unjustly neglected after his death, he has become better known in recent years, though still only for a handful of works. He was an important British composer of the twentieth century and his music deserves greater appreciation and recognition.

He was born in Brighton, being the ninth child of a modest family. His father, a keen musician, gave up his job as a printer to become a violin teacher and conductor of a theatre orchestra. Young Frank was made to learn the violin and subjected to long hours of practice. He entered the Royal College of Music and though his first few years were undistinguished, he won a scholarship to study composition with Stanford. He then developed rapidly as a composer and also took up the viola, soon becoming a fine player. On leaving the college, he earned his living as a teacher and performer. He played in three string quartets, most notably the English String Quartet which became one of the country’s finest chamber groups. At this time he composed a good deal of chamber music, along with songs, other vocal works and piano pieces. His style was easy-going, with a ready appeal to the public, and he began to make his reputation. Especially popular was his four-movement orchestral suite The Sea. He also became known as a reliable conductor, often called on to deputise at the last minute when someone was indisposed.

Then came the first world war. Bridge was a pacifist by inclination and he was horrified by the violence of the war and the slaughter in the trenches. He seems to have passed through a personal crisis and his musical style changed significantly. After the war, his music became deeper and more personal in tone. Influenced perhaps by the more modern music emerging in continental Europe, it also became more advanced and dissonant, more radical in style. At the same time, owing to the aftermath of war, Bridge found his income reduced and was forced to undertake more teaching, leaving him less time and energy for composition.

His fortunes changed with the appearance of an American patroness. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge was a wealthy heiress who spent vast sums on music, organising concerts and festivals of chamber music and commissioning new works. She met Bridge in England in 1922, they became friends, and soon Bridge and his wife joined Mrs Coolidge for a tour of France, all at her expense. The following year they sailed for New York to take part in her festival, after which Bridge enjoyed a month’s tour of America, conducting various orchestras. Though Bridge was grateful for Mrs Coolidge’s support, he did not want to become permanently indebted to her and he initially turned down her offer of an annual payment; later however, he accepted it with gratitude. Now that he had been given the gift of financial security, he could return home to England and compose as he wished.

Though his home had been for some time in London, Bridge was fond of Sussex and he enjoyed walking on the south downs. His creativity was nourished by the landscape and by its proximity to the sea, and so he and his wife had a house built near Friston with a view of the downs. Here Bridge devoted himself to composition, producing many outstanding works, such as his third and fourth string quartets, his second piano trio and violin sonata, the orchestral Enter spring and There is a willow grows aslant a brook, Phantasm for piano and orchestra, and his one-movement cello concerto Oration. These works had less appeal for the public and Bridge died in relative obscurity, aged only 62, after suffering poor health.

Alongside his achievements as a composer, now happily receiving greater recognition, Frank Bridge is also remembered as the teacher of Benjamin Britten. Britten first heard Bridge’s music as a young boy when he attended a Norwich Festival concert and heard Bridge conduct The Sea. As Britten said, he was ‘knocked sideways’ by it. A few years later he began taking composition lessons with Bridge and a close friendship developed between the two. Britten remembered his teacher as strict and demanding, one who imposed high standards, but he also enjoyed his wide-ranging conversations, embracing music, art and literature. While Britten was at the Royal College he visited the Bridges at home in London, and later Frank would drive him around Sussex, introducing him to the beauty of the countryside. Britten left a permanent musical tribute to his teacher in his orchestral Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge.

Written by Ian Codd

Action, Camera, Roll - Shooting in Surrey! (Part 1)

Perhaps it is not surprising that so many films have been shot in Surrey – beautiful countryside, historic and photogenic buildings, not far from London, and, of course, Shepperton Studios. Most are modern blockbusters, specially written to showcase a star, or recreate a series of commercially successful novels. But there are many that are adaptations of classic novels or plays – copies of which are in the library.

Here are just a few of them. When we are able to travel once more, it could be interesting to follow them up – and see whether the settings match up to those in our imaginations! If you know of any other classic films with sets from our beautiful county, please do tell us know, so that we can check our catalogue, and let everyone know.

Film Title: Dorian Gray (2009)

Author: Oscar Wilde

Location: Painshill Park, Cobham

Featuring Wimbledon born Ben Barnes in the starring role

Image: The 18th century landscape garden’s lakeside was transformed into Hampstead Heath for this adaption

While we do not have an adaptation of this particular novel in the library (yet!)– we have a wealth of other material by Oscar Wilde:

Film Title: Hound of the Baskervilles (1959)

Author: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Location: Frensham Ponds, near Farnham

Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee starred in this version of the famous Sherlock Holmes tale. Some of the filming was done at Frensham Ponds. The original book was written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at his Surrey home, 'Undershaw’.

Film Title: Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011)

Author: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Location: Richmond Park, Hampton Court Palace, in East Molesey, and Bourne Woods near Farnham, among other locations.

Features Robert Downey Jr and Jude Law as Holmes and Watson.

We have several volumes of plays adapted from Conan Doyle, perhaps to read after a visit to see his house? (Note: this is not open to the public – it is now Stepping Stones School, restored for use as a school for children with hemiplegia, physical, medical, anxiety, and autistic spectrum difficulties. The school opened in September 2016 after a full restoration of the house and the building of a contemporary extension and annex.

Written by Carol Hall

Perhaps it is not surprising that so many films have been shot in Surrey – beautiful countryside, historic and photogenic buildings, not far from London, and, of course, Shepperton Studios. Most are modern blockbusters, specially written to showcase a star, or recreate a series of commercially successful novels. But there are many that are adaptations of classic novels or plays – copies of which are in the library.

Here are just a few of them. When we are able to travel once more, it could be interesting to follow them up – and see whether the settings match up to those in our imaginations! If you know of any other classic films with sets from our beautiful county, please do tell us know, so that we can check our catalogue, and let everyone know.

Film Title: Dorian Gray (2009)

Author: Oscar Wilde

Location: Painshill Park, Cobham

Featuring Wimbledon born Ben Barnes in the starring role

Image: The 18th century landscape garden’s lakeside was transformed into Hampstead Heath for this adaption

While we do not have an adaptation of this particular novel in the library (yet!)– we have a wealth of other material by Oscar Wilde:

- A Woman of no importance Methuen [8m 7f 18copies 4 acts]

- An Ideal husband Methuen [9m 6f 18 copies 4 acts]

- The Importance of being earnest (original 4-act version) Samuel French [8m 4f 11 copies]

- The Importance of being earnest (3-act version) Samuel French [5m 4f 12copies 3 acts]

- The Importance of being earnest and other plays Penguin [6 copies] This set also includes Lady Windermere's fan, A woman of no importance, An ideal husband and Salome

- Lady Windermere's fan Methuen [7m 9f 20 copies 4 acts]

Film Title: Hound of the Baskervilles (1959)

Author: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Location: Frensham Ponds, near Farnham

Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee starred in this version of the famous Sherlock Holmes tale. Some of the filming was done at Frensham Ponds. The original book was written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at his Surrey home, 'Undershaw’.

Film Title: Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011)

Author: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Location: Richmond Park, Hampton Court Palace, in East Molesey, and Bourne Woods near Farnham, among other locations.

Features Robert Downey Jr and Jude Law as Holmes and Watson.

We have several volumes of plays adapted from Conan Doyle, perhaps to read after a visit to see his house? (Note: this is not open to the public – it is now Stepping Stones School, restored for use as a school for children with hemiplegia, physical, medical, anxiety, and autistic spectrum difficulties. The school opened in September 2016 after a full restoration of the house and the building of a contemporary extension and annex.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan Sherlock Holmes Samuel French [large cast 25copies 2 acts]

- Doyle, Arthur Conan The Speckled Band Samuel French [large cast 9 copies 3 acts]

- Hardwick, M The Game's Afoot: Sherlock Holmes plays J. Murray [13copies]

- Hardwick, M Four More Sherlock Holmes Plays J. Murray [12 copies]

- Ron Nichol, The Man who Collected Women. This is a one act play based on Conan Doyle’s short story The Illustrious Client [10 copies]

Written by Carol Hall

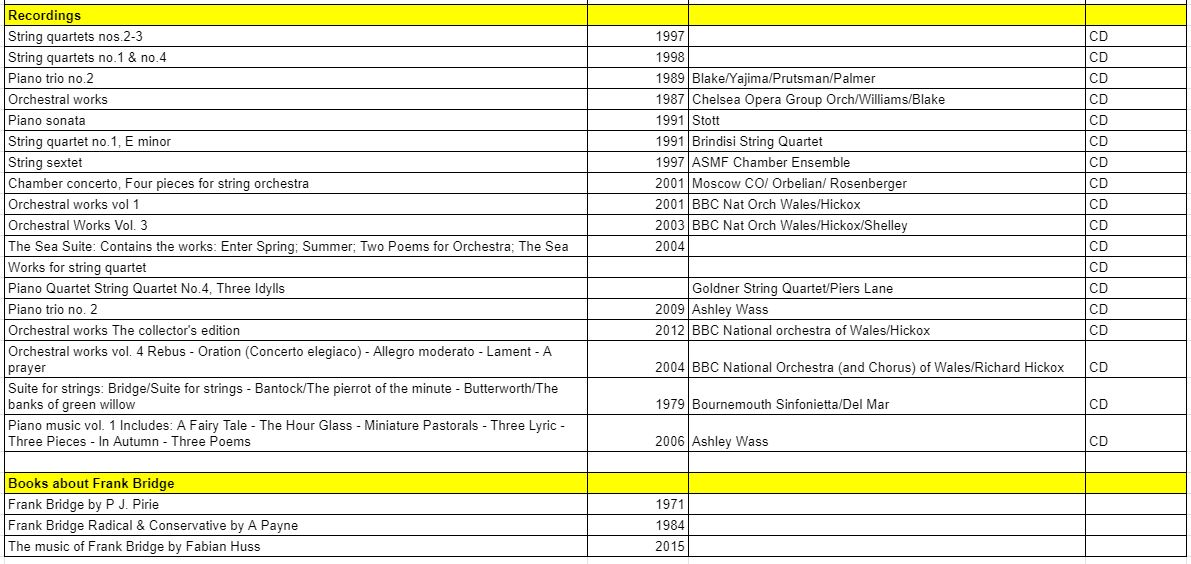

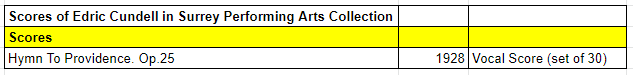

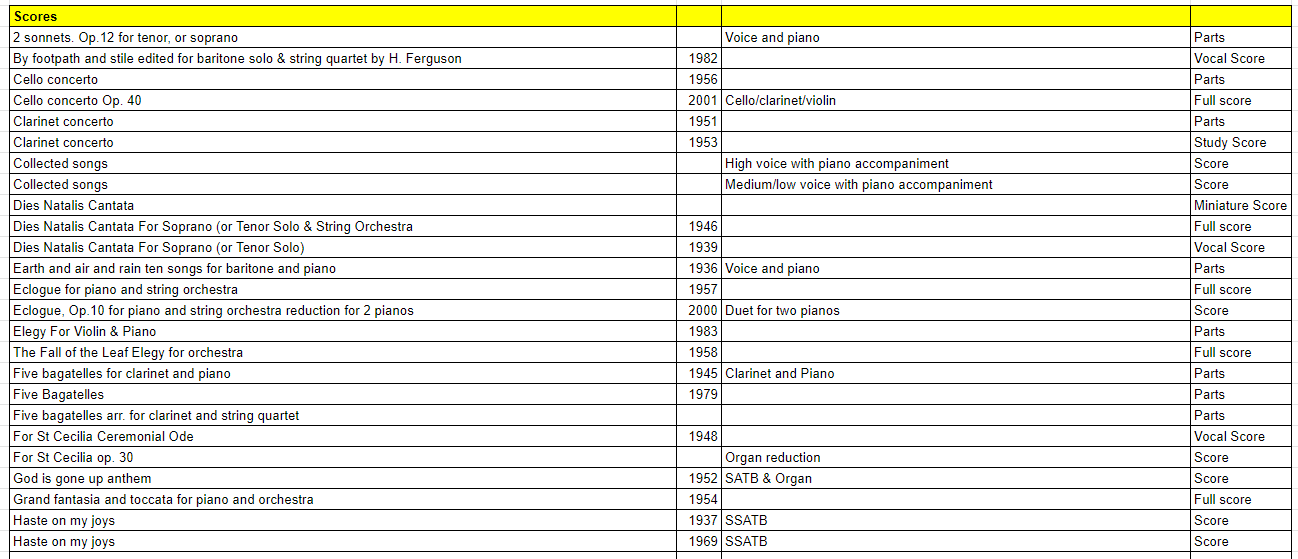

Edric Cundell: Remembering a forgotten but influential musician

Amongst the many scores by the great composers of the classical canon in the Surrey Performing Arts Library collection there are a few sets by less familiar names. For example, the small pile of 30 vocal scores of Hymn to Providence for chorus and orchestra, op. 25 by Edric Cundell, a setting of the opening section of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Ode on the Departing Year.

So, who was Edric Cundell?

In May 1940 the British Government, threatened by invasion, suddenly ordered a mass internment of ‘enemy aliens’, many of whom were refugees from Nazi Germany. Churchill famously said “Collar the lot.” In August, motivated by the situation of his Dorking neighbour Robert Müller-Hartmann - many of the internees were blameless and held in very poor conditions - Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote to the prominent musician Granville Bantock to ask for his support in pressing the Government to release interned musicians, copying the letter to a group of people who it can be assumed he considered to be the leading members of the British musical establishment of the time. Along with names still well-known, such as Walford Davies, Adrian Boult and William Walton, the recipients included Edric Cundell.

Cundell was the Principal of the Guildhall School of Music, a post that he had been appointed to in 1938. A pen portrait published in the Musical Times on his retirement in 1959 describes his contribution to the development of the school, in particular the improvement in the quality of its opera productions, despite the privations of the second world war and its aftermath. Cundell’s background as a practising musician, conductor and composer is noted, as is his sympathy for amateur music-making through his work with summer schools and as an adjudicator for music festivals. He is described as a ‘very good committee man’.

The pen portrait mentioned that he had served with the Army in Serbia during the first world war. Indeed, while he was on active service in 1917 attached to the Serbian Army he had composed a symphonic poem ‘Serbia’. According to a Radio Times listing for a 1937 broadcast, the work was written ‘in a dug-out, close to the Bulgarian lines’ and was based on ‘folk songs, which the Serbian soldiers used to sing during the time of their great trial, following their tragic retreat over the Albanian mountains’. The work was first performed at Salonika by the Royal Orchestra of Prince Alexander of Serbia to whom it was dedicated. ‘Serbia’ was performed at the Proms on the 21st September 1921, conducted by Cundell himself, and would have been played again on 20th September 1940 had not the performance been cancelled because of the Blitz.

The British Army medal card of Lieutenant Cundell of the Royal Army Service Corps documents his service in Salonika from September 1916. However, it also records something else. The original surname on the card, Greiffenhagen, is crossed out and replaced with Cundell, with a note that his surname had been changed. During the First World War anti-German sentiment in Britain reached an hysterical level with rioting and attacks on those with German sounding names, many of whom followed the example of George V who changed his family name from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to Windsor.

The surname Cundell came from Edric’s paternal grandmother, Helen Cundell. Edric’s paternal grandfather, Augustus Samuel Greiffenhagen, came to England in 1846 from Russia. By the 1851 census he claimed already to be a naturalised British Subject and in the 1871 census he gave his place of birth as Archangel, in the north of European Russia. In May 1851 Augustus married Helen Cundell, the daughter of Stewart Cundell, a druggist and the manufacturer of Cundell’s Balsam of Honey. Helen (or Hélène) was an operatic soprano with a career in mainland Europe and Britain, as was also her sister Elizabeth Blenkarn Cundell. Later as Madame Greiffenhagen she practised as a Professor of Singing in London. There is a detailed article about Hélène and Elizabeth in Kurt Gänzl’s ‘Victorian Vocalists’[1]. Augustus Samuel and Hélène’s eldest son was Henry Cundell Grieffenhagen who married Harriett Mary Ann Stevens in 1880. Their youngest son and fifth child Edric was born in 1893.

In the 1911 census the eighteen-year-old Henry Edric Arnold Greiffenhagen is described as a ‘Musical Student of French Horn and composition’. Edric studied the horn with Thomas Busby and, according to some accounts, Adolph Borsdorf, both of whom were founding members of the London Symphony Orchestra. A 1936 Radio Times listing states that he played at Covent Garden in 1912 under the celebrated conductor Arthur Nikisch; the involvement of the nineteen-year-old Cundell would probably been through his connection with Borsdorf and Busby. Borsdorf, originally from Hamburg but a naturalised British citizen, would himself become a victim of anti-German feeling and in 1915 he was forced to resign his membership of the LSO. Borsdorf’s sons, who were serving with the British Army, like Cundell changed their surname, in their case to Bradley.

Sadly, Cundell’s retirement was not to last long. He died in 1961 at the age of 68. His obituary, again from the Musical Times, describes his appointment to the Guildhall post as a bold one but that he had left behind him a ‘tradition of high standards and hard work happily undertaken’ which had produced a large number of successful singers. His composing career was also recognised; his String Quartet Op. 27 had won the prize in a Daily Telegraph competition in 1933[2]. He had been on the staff of Trinity College of Music, where he had previously been a student, from 1920 and was the conductor of a number of amateur orchestras and well as his own professional orchestra, which broadcast regularly between 1935 and 1939. During and after WW2 he also regularly conducted and broadcast with the major London orchestras, including the LSO, the LPO, and the BBCSO. He had served on the committees of the Royal Philharmonic Society, the Royal Musical Association, the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund and the Arts Council. and had also been a director of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He is summed up as a man of the utmost integrity, wide sympathies and common sense with a quiet manner concealing a strong and attractive personality. He was awarded the CBE in 1949. He married the sculptor Helena Scott in 1920 and they had one son, born in 1936.

As Principal of the Guildhall School of Music, Cundell would have influenced the careers of many hundreds of musicians. However, there was one decision that he made that was to have unusually significant consequences. In 1947 a recently demobilised young man with a natural talent but no formal training and who was lacking in self-belief was persuaded to go for an interview with Edric Cundell with a view to taking up music as a career. Cundell, after hearing him play his compositions, accepted him on a three year ‘Course for Teachers’. The young man’s name was George Martin who went on to become a rather successful record producer.

Footnotes

[1] Victorian Vocalists Kurt Ganzl (Taylor & Francis 2017) Link

[2] The competition had excited interest amongst a number of young British composers. Elizabeth Maconchy and Grace Williams’ gossipy letters about it can be read in Music, Life, and Changing Times: Selected Correspondence Between British Composers Elizabeth Maconchy and Grace Williams, 1927–77 ed Sophie Fuller and Jenny Doctor (Routledge 2019) Link . The semi-finalists were played for the judges without identification which led to much speculation as to who had written what. The second and third prizes behind Cundell were won by Cecil Armstrong Gibbs and Maconchy with her Quintet for oboe and strings. Benjamin Britten’s Phantasy for oboe and string trio and Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s Sextet were Highly Commended. Williams’ Sextet for oboe, trumpet, violin, viola, cello and piano was unplaced. Williams tells Maconchy: ‘My dear, Benjamin once heard some Cundell … and he says it was frightful. Brahms and Elgar.”

Copies of some of Cundell’s published compositions are held by the British Library including:

String Quartet Op. 18 (1923)

Sonnet: Our Dead (1929) for tenor and orchestra. Text by Robert Nicols

String Quartet in C Op. 27 (1933)

Two pieces for Brass Quartet (1957)

As well as a number of songs and short vocal pieces, and original compositions and transcriptions for solo piano

His varied output also included a Symphony Op. 23, a Piano Concerto, two symphonic poems The Tragedy of Deirdre and Serbia, an unaccompanied Mass, a Piano Quartet and three string quartets.

Recordings on YouTube

As a composer

Symphonic Prelude: ‘Blackfriars’ written as a test piece for the 1955 National Brass Band Championships and arranged by the brass band specialist Frank Wright who was Cundell’s colleague at the Guildhall School of Music. link.

Aquarelle for piano link

As a conductor

Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 Peter Katin (piano) New Symphony Orchestra of London in four parts: 1, 2, 3, 4.

Written by Roger Miller.

Amongst the many scores by the great composers of the classical canon in the Surrey Performing Arts Library collection there are a few sets by less familiar names. For example, the small pile of 30 vocal scores of Hymn to Providence for chorus and orchestra, op. 25 by Edric Cundell, a setting of the opening section of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Ode on the Departing Year.

So, who was Edric Cundell?

In May 1940 the British Government, threatened by invasion, suddenly ordered a mass internment of ‘enemy aliens’, many of whom were refugees from Nazi Germany. Churchill famously said “Collar the lot.” In August, motivated by the situation of his Dorking neighbour Robert Müller-Hartmann - many of the internees were blameless and held in very poor conditions - Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote to the prominent musician Granville Bantock to ask for his support in pressing the Government to release interned musicians, copying the letter to a group of people who it can be assumed he considered to be the leading members of the British musical establishment of the time. Along with names still well-known, such as Walford Davies, Adrian Boult and William Walton, the recipients included Edric Cundell.

Cundell was the Principal of the Guildhall School of Music, a post that he had been appointed to in 1938. A pen portrait published in the Musical Times on his retirement in 1959 describes his contribution to the development of the school, in particular the improvement in the quality of its opera productions, despite the privations of the second world war and its aftermath. Cundell’s background as a practising musician, conductor and composer is noted, as is his sympathy for amateur music-making through his work with summer schools and as an adjudicator for music festivals. He is described as a ‘very good committee man’.

The pen portrait mentioned that he had served with the Army in Serbia during the first world war. Indeed, while he was on active service in 1917 attached to the Serbian Army he had composed a symphonic poem ‘Serbia’. According to a Radio Times listing for a 1937 broadcast, the work was written ‘in a dug-out, close to the Bulgarian lines’ and was based on ‘folk songs, which the Serbian soldiers used to sing during the time of their great trial, following their tragic retreat over the Albanian mountains’. The work was first performed at Salonika by the Royal Orchestra of Prince Alexander of Serbia to whom it was dedicated. ‘Serbia’ was performed at the Proms on the 21st September 1921, conducted by Cundell himself, and would have been played again on 20th September 1940 had not the performance been cancelled because of the Blitz.

The British Army medal card of Lieutenant Cundell of the Royal Army Service Corps documents his service in Salonika from September 1916. However, it also records something else. The original surname on the card, Greiffenhagen, is crossed out and replaced with Cundell, with a note that his surname had been changed. During the First World War anti-German sentiment in Britain reached an hysterical level with rioting and attacks on those with German sounding names, many of whom followed the example of George V who changed his family name from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to Windsor.

The surname Cundell came from Edric’s paternal grandmother, Helen Cundell. Edric’s paternal grandfather, Augustus Samuel Greiffenhagen, came to England in 1846 from Russia. By the 1851 census he claimed already to be a naturalised British Subject and in the 1871 census he gave his place of birth as Archangel, in the north of European Russia. In May 1851 Augustus married Helen Cundell, the daughter of Stewart Cundell, a druggist and the manufacturer of Cundell’s Balsam of Honey. Helen (or Hélène) was an operatic soprano with a career in mainland Europe and Britain, as was also her sister Elizabeth Blenkarn Cundell. Later as Madame Greiffenhagen she practised as a Professor of Singing in London. There is a detailed article about Hélène and Elizabeth in Kurt Gänzl’s ‘Victorian Vocalists’[1]. Augustus Samuel and Hélène’s eldest son was Henry Cundell Grieffenhagen who married Harriett Mary Ann Stevens in 1880. Their youngest son and fifth child Edric was born in 1893.

In the 1911 census the eighteen-year-old Henry Edric Arnold Greiffenhagen is described as a ‘Musical Student of French Horn and composition’. Edric studied the horn with Thomas Busby and, according to some accounts, Adolph Borsdorf, both of whom were founding members of the London Symphony Orchestra. A 1936 Radio Times listing states that he played at Covent Garden in 1912 under the celebrated conductor Arthur Nikisch; the involvement of the nineteen-year-old Cundell would probably been through his connection with Borsdorf and Busby. Borsdorf, originally from Hamburg but a naturalised British citizen, would himself become a victim of anti-German feeling and in 1915 he was forced to resign his membership of the LSO. Borsdorf’s sons, who were serving with the British Army, like Cundell changed their surname, in their case to Bradley.

Sadly, Cundell’s retirement was not to last long. He died in 1961 at the age of 68. His obituary, again from the Musical Times, describes his appointment to the Guildhall post as a bold one but that he had left behind him a ‘tradition of high standards and hard work happily undertaken’ which had produced a large number of successful singers. His composing career was also recognised; his String Quartet Op. 27 had won the prize in a Daily Telegraph competition in 1933[2]. He had been on the staff of Trinity College of Music, where he had previously been a student, from 1920 and was the conductor of a number of amateur orchestras and well as his own professional orchestra, which broadcast regularly between 1935 and 1939. During and after WW2 he also regularly conducted and broadcast with the major London orchestras, including the LSO, the LPO, and the BBCSO. He had served on the committees of the Royal Philharmonic Society, the Royal Musical Association, the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund and the Arts Council. and had also been a director of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He is summed up as a man of the utmost integrity, wide sympathies and common sense with a quiet manner concealing a strong and attractive personality. He was awarded the CBE in 1949. He married the sculptor Helena Scott in 1920 and they had one son, born in 1936.

As Principal of the Guildhall School of Music, Cundell would have influenced the careers of many hundreds of musicians. However, there was one decision that he made that was to have unusually significant consequences. In 1947 a recently demobilised young man with a natural talent but no formal training and who was lacking in self-belief was persuaded to go for an interview with Edric Cundell with a view to taking up music as a career. Cundell, after hearing him play his compositions, accepted him on a three year ‘Course for Teachers’. The young man’s name was George Martin who went on to become a rather successful record producer.

Footnotes

[1] Victorian Vocalists Kurt Ganzl (Taylor & Francis 2017) Link

[2] The competition had excited interest amongst a number of young British composers. Elizabeth Maconchy and Grace Williams’ gossipy letters about it can be read in Music, Life, and Changing Times: Selected Correspondence Between British Composers Elizabeth Maconchy and Grace Williams, 1927–77 ed Sophie Fuller and Jenny Doctor (Routledge 2019) Link . The semi-finalists were played for the judges without identification which led to much speculation as to who had written what. The second and third prizes behind Cundell were won by Cecil Armstrong Gibbs and Maconchy with her Quintet for oboe and strings. Benjamin Britten’s Phantasy for oboe and string trio and Victor Hely-Hutchinson’s Sextet were Highly Commended. Williams’ Sextet for oboe, trumpet, violin, viola, cello and piano was unplaced. Williams tells Maconchy: ‘My dear, Benjamin once heard some Cundell … and he says it was frightful. Brahms and Elgar.”

Copies of some of Cundell’s published compositions are held by the British Library including:

String Quartet Op. 18 (1923)

Sonnet: Our Dead (1929) for tenor and orchestra. Text by Robert Nicols

String Quartet in C Op. 27 (1933)

Two pieces for Brass Quartet (1957)

As well as a number of songs and short vocal pieces, and original compositions and transcriptions for solo piano

His varied output also included a Symphony Op. 23, a Piano Concerto, two symphonic poems The Tragedy of Deirdre and Serbia, an unaccompanied Mass, a Piano Quartet and three string quartets.

Recordings on YouTube

As a composer

Symphonic Prelude: ‘Blackfriars’ written as a test piece for the 1955 National Brass Band Championships and arranged by the brass band specialist Frank Wright who was Cundell’s colleague at the Guildhall School of Music. link.

Aquarelle for piano link

As a conductor

Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 Peter Katin (piano) New Symphony Orchestra of London in four parts: 1, 2, 3, 4.

Written by Roger Miller.

Gerald Finzi (1901-1956)

Gerald Finzi had a keen awareness of life’s transience and fragility. His own father died when Gerald was only eight, his three elder brothers predeceased him, and he was deeply upset when his music teacher was killed in 1918, shortly after going to fight in France. This sense of loss was expressed in his best music and especially in his songs, which rank as some of the finest in the English language.

Finzi’s parents were Jewish, with his paternal ancestors originating in Italy. His father was a prosperous businessman with the result that Finzi had no need to work for a living. From a young age he devoted himself to music. After a period of some private study he went to live in London where he began to move in musical and artistic circles, came to know such figures as Holst and Vaughan Williams, and tried to establish himself as a composer.

He met and married Joyce, an artist and poet, and together they designed and had built a substantial house high in the Hampshire hills. There Gerald was able to compose and to pursue his other passion, for literature. He amassed an impressive music library and also a fine collection of English literature and poetry; after his death both collections were housed in university libraries. He also created an orchard of rare apple trees, preserving many varieties from extinction in the process. From the age of fifty he lived with the knowledge that he suffered from leukaemia and had only years to live. In the event, it was shingles that actually killed him, aided by his weakened level of resistance.

With his love of literature, Finzi had a fine sensitivity to English words and he excelled in vocal music, especially song. The poetry of Thomas Hardy particularly appealed to him and he made many fine settings, gathered together in such collections as A young man’s exhortation and Earth and air and rain. Many of these songs express his sense of loss, and his awareness of time passing and the precarious nature of life. His vocal lines are never elaborate or florid, but always shaped so as to convey the meaning of the words. They are mostly syllabic, rarely decorative and often very moving. Two larger vocal works are particularly distinguished: his choral setting of Wordsworth’s ode Intimations of Immortality, and Dies Natalis, based on poems by Thomas Traherne. Both of these celebrate the innocence of childhood and the adult’s sense of loss and exclusion from this Eden.

Though Finzi was introspective and withdrawn by nature, he and Joyce had a circle of friends whom they often entertained at their house. He founded a semi-amateur string orchestra, the Newbury String Players, which he conducted, and through which he supported and encouraged young composers and performers. He undertook research into eighteenth-century English music, resulting in some editions, and he fought hard to make the music of the war-damaged Ivor Gurney better known.